The merger control regime under the Trade Competition Act, B.E. 2560

(2017) has been in full effect since the end of 2018 due to the

promulgation of all relevant subordinate legislation.

Merger control and clearance has developed into a major international

issue for companies looking to merge operations across different

jurisdictions. Numerous countries have taken a proactive stance on

merger filing in M&A and have established laws and guidelines

concerning merger clearance. The stakes are now higher and the

penalties stronger as more countries employ greater scrutiny over merger

deals.

Part 1: What type of transaction triggers filing?

The Thai merger control regime covers both asset deals and share deals.

Based on the relevant notifications, the following types of transaction are

deemed to be “mergers” and will be subject to a materiality test.

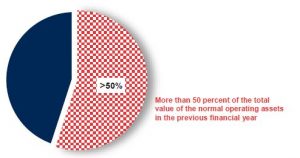

Asset acquisition

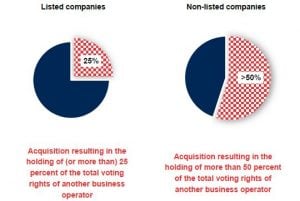

Share acquisition

Even if a transaction could be considered purely domestic, the transaction has the potential to trigger merger filings in other jurisdictions. This usually occurs when one or more of the merging parties are involved in sales outside of their jurisdictions, such as by exporting products. In such circumstances, the merger could have an impact on competition in another market outside of the merging party’s country. Due to the increasing scrutiny and nature of globalised business, it is essential that parties conduct multi-jurisdictional merger control analysis to determine which jurisdictions may require merger control.

How the Office of the Trade Competition Commission (the “OTCC“) will apply these rules in practice remains to be seen. For example, based on the way the merger regulation is drafted, the establishment of a greenfield joint venture might not even be considered a “merger.” Also, it is still unclear whether certain common forms of transaction (such as a merger at the level of the offshore parent companies or a share acquisition at the holding-company level) would be subject to the Thai merger control regime.

Part 2: Transaction threshold

According to the Thai Competition Act and subordinate legislation on merger control, the Thai merger control regime has two compliance levels, depending on the effects of the transaction: pre-merger approval and post-merger report.

a. Pre-merger approval

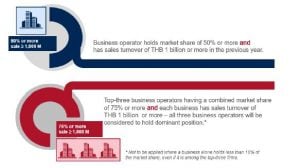

A merger resulting in a monopoly or a business operator holding a dominant position must obtain prior approval from the Trade Competition Commission.

Monopoly

Business operator holding a dominant position

b. Post-merger Notification

A merger resulting in the significant lessening of competition in the market must be reported to the Trade Competition Commission within seven days from the date of the merger.

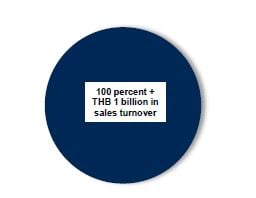

A merger resulting in the substantive lessening of competition in the market is defined as a merger in which the combined sales turnover of the merging business operators reaches Baht 1 billion or more, but the merger does not result in a monopoly or the business operator holding a dominant position.

How could merger control affect the transaction timeline?

Merger control filing is often a long process. Using Thailand as an example, the regulator’s consideration can take up to 90 days (and could be extendable by another 15 days), without taking the timing for merger control analysis and the time necessary to prepare and collect all required information for the filing into account. The OTCC may not officially “start the clock” until all of the required information and reports are submitted.

Also, the application for pre-merger filing for Thailand requires extensive information and documents and analysis to illustrate the market structure and potential impact on the market. It is usually prudent to start early to allow time for all of the team to assemble the required information, especially if the transaction requires filing in more than one jurisdiction.