In brief

HMRC has published its response to the recent consultation on the operation of the UK hybrid-mismatch rules along with draft legislation to amend the rules in various respects. Although the consultation document identified discrete areas where HMRC were seeking views, HMRC also welcomed broader feedback on the current operation of legislation to the extent it was not operating proportionately or as intended.

HMRC’s proposals only offer partial solutions to many of the issues identified by stakeholders. In particular, US multinational groups may continue to suffer material disallowances under the double deduction rules in some common (and benign) commercial structures. It is clear from our recent discussions with HMRC that they have endeavored strike a balance between fixing some of the issues with the current legislation while ensuring the rules cannot be manipulated. The remaining pitfalls within the legislation which continue to lead to economic double taxation are therefore deliberate policy choices that HMRC intends to stick by irrespective of the harmful consequences for some taxpayers.

The only area where the position is expected to change as compared with the recently published draft legislation is in relation to the repeal of s.259ID. As originally announced, s.259ID is to be repealed retroactively and this will result in some taxpayers being worse off where they cannot rely on the new broader definition of dual inclusion income (which similarly will have retroactive effect). We understand this issue may be resolved, with HMRC suggesting that the legislation may be amended so that taxpayers have an option to continue relying on s.259ID until the date of Royal Assent of the next Finance Act. HMRC has warned that they anticipate closely reviewing those structures unable to rely to on broader definition of dual inclusion income so the reprieve may be short lived.

This policy position will come as a blow to US multinational groups who run the risk of suffering material disallowances in commercially driven structures that do not achieve any form of tax advantage. This only serves to weaken the UK as investment destination with other jurisdictions such as Ireland appearing more willing to take a pragmatic approach to account for the overlay of US taxation.

Key takeaways

- Following the outcome of a recent consultation on the operation of the UK hybrid-mismatch rules a number of legislative changes have been announced. Whilst the majority of measures are intended to be favourable, some may leave taxpayers worse off, with common arrangements that give rise to economic double taxation left unaddressed.

- The definition of dual inclusion income is to be broadened to capture income that is subject to inclusion in the UK without deduction anywhere else (e.g. payments from a US parent to a checked open UK subsidiary). This will apply with retroactive effect from 1 January 2017; HMRC have indicated that they are exploring ways to allow taxpayers to re-open closed returns to apply this retroactive change.

- S.259ID, introduced in 2018 to try and correct double deduction issues, is to be scrapped. HMRC’s response to the consultation indicated this would be applied retroactively. However, we understand that the intention is for the draft legislation to be amended to introduce optionality such that taxpayers can continue to apply s.259ID until the date of Royal Assent of the next Finance Act.

- Checked open UK companies still face a denial of deductions where their only source of income is from checked open group subsidiaries that are resident outside the UK and the US.

- A new surrender mechanism for “surplus” dual inclusion income is to be introduced. This will allow entities within a group relief group to use dual inclusion income arising in one entity against counteractions in another. It is intended that this will apply from 1 January 2021.

- The illegitimate overseas deduction rules within Chapters 9 and 10 are to be narrowed, only taking effect where double deductions are offset against income arising to an entity that is external to the hybrid structure. The narrowing will not take effect until the date of Royal Asset.

- In their response to consultation, HMRC point to this new surrender mechanism and narrower definition of illegitimate overseas deductions as aiding issues arising from the interaction of the UK hybrid-mismatch rules and the US dual consolidated loss (DCL) rules. However, as those changes will not take effect until 2021, disallowances that have arisen between 2017 and 2020 will remain unresolved. HMRC have indicated that they are in discussion with IRS on this point and are hopeful of reaching a positive outcome for taxpayers through guidance. However, they are unlikely to be able to publish amended guidance until mid-2021.

- There are both positive and negative changes to the imported mismatch rule under Chapter 11, which take effect from the date of Royal Assent. Going forward, the imported mismatch provisions will only require a foreign regime to be equivalent to the UK rules to switch off a counteraction (instead of requiring the foreign regime to apply similar provisions to the relevant part of the UK rules). However, Condition F, which provided taxpayers with a degree of protection against a counteraction by allowing consideration of UK tax attributes to negate a foreign mismatch payment, is to be scrapped.

- HMRC has decided not to recognise income subject to GILTI in the US as ‘ordinary income’ for purposes of the hybrid-mismatch rules. Although the consultation document acknowledges that this approach has the potential to lead to economic double taxation, HMRC has decided that it is too complex to legislate to resolve this issue. This is disappointing and does not accord with the position taken by other EU countries that have implemented hybrid-mismatch rules.

Continued double taxation of US multinationals – disregarded payments

The mechanical operation of the double deduction rules contained in Chapter 9 of the UK’s hybrid-mismatch rules can lead to potentially material disallowances and effective double taxation for taxpayers. In particular, where UK subsidiaries which have been checked open incur costs from third parties, whilst only receiving intra-group income from transactions that are disregarded for US tax purposes.

An attempt to address this issue was made through the introduction of ‘s.259ID income’ in Finance Act 2018. This enabled payments to checked open UK subsidiaries to be treated as akin to dual inclusion income for the purposes of Chapter 9 where there was a certain degree of connection between that payment and third party income received by the group. In interpreting the provision HMRC appeared to apply a very narrow reading, which seemingly conflicted with the broader interpretation applied by taxpayers in filing positions adopted on the point.

HMRC had initially intended to repeal s.259ID retroactively, removing all traces of it from the statute books. However, having received feedback that there are a number of taxpayers that have placed reliance on s.259ID who are unable to satisfy the conditions of the broader definition of dual inclusion income introduced in its place, HMRC have indicated that optionality may be embedded within the re-write. Between the 1 January 2017 and the date of Royal Asset of the next Finance Act taxpayers may have the choice to continue to apply the s.259ID income concept or the new broader definition of dual inclusion income, but not both.

Notwithstanding this, HMRC indicated that their expectation is that the broader definition of dual inclusion income should capture all of the circumstances where s.259ID applies. However, they recognise that disputes over the proper application of s.259ID should take place through the court and tribunal system, not circumvented through retroactive repeal. The continued application of s.259ID should therefore become a significant risk indicator for HMRC.

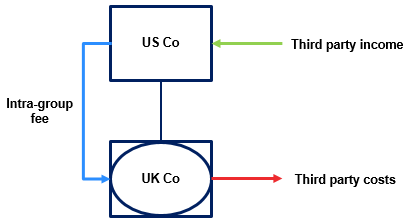

Like s.259ID, the new broader definition of dual inclusion income will allow certain payments that are subject to a single inclusion to be treated as though they are dual inclusion income. Where a payment is made to a UK hybrid entity that is taxable in its hands and not deductible in any other jurisdiction, but would have been deductible in another jurisdiction were the UK entity not a hybrid entity, it is treated as though it is dual inclusion income. This should therefore allow the intra-group fee in the diagram below to be regarded as dual inclusion income, thereby negating the double deduction that arises in respect of the third party costs.

Whilst this will be welcome news for some taxpayers, others remain left out in the cold. Common structures that involve transactions between a checked open UK subsidiary and a subsidiary that is also checked open, but resident in neither the US nor the UK, continue to face economic double taxation.

In the diagram above the US disregards the intra-group fee and treats US Co as though it had received the third party costs and income. Non-UK Co should be taxed on the third party income and receive a deduction for the intra-group fee. However, UK Co stands to be taxed on the intra-group fee with no relief available for its costs. This is on the basis that the third party costs are deductible both in the UK and the US and should therefore constitute hybrid entity double deductions. The intra-group fee is not dual inclusion income in the ordinary sense as it is subject to a single level of taxation in the UK on account of being disregarded for US purposes. Likewise, the intra-group fee is unlikely to meet the new broader definition of dual inclusion income as the deduction of the intra-group fee in the hands of Non UK Co taints the position. This therefore leaves the structure facing double taxation with the UK taxed on its gross revenue.

HMRC’s comments in their response to the consultation suggest a nervousness to adopting similar relieving provisions without a legislative mechanism that mechanically proves on its own terms that there is double taxation of third party income outside the UK. In the example above, that would be a legislative test that captures the double taxation of Non-UK Co’s third party income, offsetting the double deduction of costs in the UK.

In our discussions with HMRC, they also indicated that issues around enforcement of information notices in respect of non-UK transactions are a practical concern for such relieving measures. If that is true, it is hard to see how the Imported Mismatch rules under Chapter 11 are workable given their operation is entirely contingent on mismatches arising from non-UK transactions.

By contrast, Ireland, which recently enacted hybrid-mismatch legislation in line with its obligations under the EU’s anti-tax avoidance directive (the ATAD), has adopted a far more pragmatic approach. Under its implementation of the rules it treats the receipt of a payment that is disregarded for the purposes of the investor jurisdiction as though it is dual inclusion income. Applied to the example above, since the intra-group fee received by UK Co is disregarded for US purposes, it would be regarded as dual inclusion income under the Irish rules, thereby curing the double deduction arising in respect of the third party costs.

The Irish rules are subject to a principles based limitation that switches off the treatment of the disregarded payment as dual inclusion income where it in substance constitutes a hybrid mismatch, either within the meaning of the ATAD or the OECD’s Final Report on Neutralising the Effects of Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development of 5 October 2015 (the Action 2 report). This strikes a sensible balance between alleviating double taxation whilst providing a legislative defence against broader mismatch arrangements.

Continued double taxation of US multinationals – dual consolidated losses

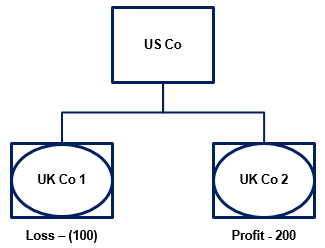

A further issue faced by US groups has been the application of the US’s DCL rules to UK subsidiaries checked into the same US parent. In the example below, UK Co 1 has a loss of (100) for the period, whilst UK Co 2 has a profit of 200. As both are checked into the same US entity for US tax purposes, the profit and loss will be automatically offset against each other to arrive at a net profit of 100 for the UK combined separate unit.

Under the current rules this triggers a counteraction under Chapter 9 as UK Co 1’s loss is deducted both in the UK and the US, and the income it is deducted against is not dual inclusion income of UK Co 1 (it is dual inclusion income of UK Co 2). The counteraction is not simply a timing issue, as UK Co 1’s deduction is offset against income which is not dual inclusion income of UK Co 1, it is treated as an ‘illegitimate overseas deduction’ and therefore permanently disallowed. This therefore means that the group is subject to double taxation as the UK group is taxed on profits of 200 despite a net economic return of 100.

HMRC has developed a solution to this issue by proposing to implement a new group relief mechanism that allows ‘surplus’ dual inclusion income of one entity to be surrendered to a fellow member of a group relief group who has a shortfall of dual inclusion income and would face a counteraction under the rules absent the surrender. Applied to the example above, UK Co 2 can surrender 100 of its 200 of surplus dual inclusion income to UK Co 1 to cover its shortfall of 100, thereby avoiding a counteraction.

We welcome this approach; however, we question why the change will only take effect from 1 January 2021. This in effects condemns taxpayers, who incur illegitimate overseas deductions through the operation of the DCL rules, to double taxation for the 4 years between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2020.

During our discussions with HMRC they indicated that they are in discussions with the IRS on this point and are hopeful of reaching a positive outcome for taxpayers through guidance, which they expect to be released around mid-2021. Whilst this is encouraging, taxpayers need clarity for pre-2021 returns now as the opportunities to adjust prior period positions grow ever smaller. Moreover, it is interesting that HMRC consider the issue can be addressed through guidance; a number of taxpayers have struggled to read the legislation in a way that does not give rise to economic double taxation.

Narrowing of illegitimate overseas deduction, but not far enough?

Whilst draft legislation has not yet been published, HMRC has indicated that it intends to narrow the definition of illegitimate overseas deduction. As discussed above in relation to issues with US DCL rules, a double deduction that is deducted against anything other than dual inclusion income of the entity constitutes an illegitimate overseas deduction and is therefore permanently disallowed.

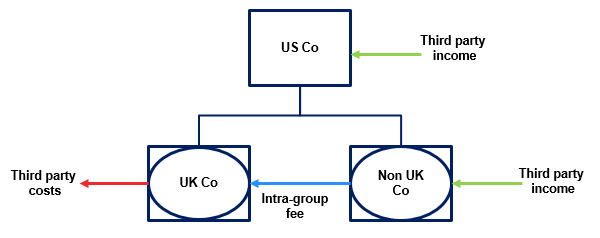

HMRC has indicated that legislation will be introduced to ensure amounts which are deducted against income of the investor in the case of Chapter 9, and the dual resident company or the multinational company in the case of Chapter 10, shall not constitute illegitimate overseas deductions. Applied to the example below, if the third party costs are deducted against the third party income directly received by US Co then it should not constitute an illegitimate overseas deduction under the proposals suggested in the response to the consultation. However, if the third party costs are deducted against the third party income received by Non UK Co, in HMRC’s view, it would continue to be an illegitimate overseas deduction and therefore be subject to permanent counteraction.

In this example, to the extent that the third party costs are offset against US Co’s third party income for US tax purposes, they are subject to deferral for UK tax purposes as the double deduction that arises in respect of them must be cured by dual inclusion income (either received by UK Co directly, or surrendered to it under the new group relief mechanism). However, if the third party costs are deducted against Non UK Co’s third party income for US tax purposes, notwithstanding the fact that this is dual inclusion income (albeit not UK dual inclusion income), it would be subject to permanent counteraction. This would leave UK Co to face double taxation as it would be taxed in full on its gross income – the intra-group fee. This arbitrary approach is difficult to reconcile to the Action 2 report which recommended that “adjustment[s] should be no more than is necessary to neutralise the hybrid mismatch and should result in an outcome that is proportionate and that does not lead to double taxation.”

Imported mismatches – Good and bad

HMRC has indicated in their response to the consultation that they intend to narrow the drafting of Condition E of the imported mismatch test under s.259KA, whilst repealing Condition F.

The narrowing of Condition E is welcome news – this in effect ensures that the UK respects jurisdictions that adopt hybrid-mismatch rules consistent with the recommendations of the Action 2 report. Condition E as currently drafted asks whether the overseas regime has similar provisions to the UK rules in order to give credit for their application and switch off a counteraction under Chapter 11. Therefore, where the UK has gone beyond the recommendations of the Action 2 report in respect of a particular mismatch, Condition E requires other jurisdictions to have done the same in order to obtain credit for their application. The recast Condition E will simply ask whether the regime as a whole is equivalent, which in effect asks is the regime based on the Action 2 report.

Taking the example of the Irish approach to treating disregarded payments as dual inclusion income discussed earlier, Condition E as currently drafted would seemingly not respect Ireland’s treatment of that particular fact pattern as it goes beyond what the UK permits. However, once re-drafted, on the assumption that HMRC accepts that the Irish rules are based on the Action 2 report, the application of those rules to an arrangement that includes a mismatch payment should be sufficient to switch off a counteraction under Chapter 11. This amendment is indicated as taking effect from Royal Assent which, assuming will be some time in 2021, raises questions as to how Chapter 11 will interact with EU regimes, such as the Irish rules, which entered into force on 1 January 2020.

A legislative change that flips the UK rules mid accounting period into respecting the approach adopted by other jurisdictions gives a strange result. However, in our discussions with HMRC they noted that they regard this as a legitimate change in policy, and therefore it is proper that it should be reflected on a prospective basis. Whilst that may be true, it is disappointing that they did not come to this realisation before our European cousins began to implement their own Action 2 compliant regimes.

The second proposed change, the repeal of Condition F, is less welcome news. Condition F asks whether the UK taxpayer that is party to the overarching arrangement would be subject to counteraction were it directly party to the foreign mismatch payment. A natural reading of this provision invites taxpayers to take into account the particular attributes of the UK entity, e.g. the existence of dual inclusion income, in making that assessment. The response to the consultation suggests HMRC agrees with that reading and therefore wants to remove this get-out for taxpayers.

In the diagram below, Non-UK Co is resident in a jurisdiction that has not implemented the recommendations of the Action 2 report into its domestic law; it therefore imposes no constraint on the double deduction that arises in respect of the third party costs. The payment of the intra-group fee by UK Co in effect funds the payment of those third party costs. Conditions A – E of the imported mismatch test under section 259KA should therefore be met; it is only Condition F of that test which currently prevents an imported mismatch from arising. Condition F asks whether UK Co would be subject to the counteraction were it directly party to the mismatch payment, i.e. UK Co incurs the third party costs directly. As noted above, a natural reading of Condition F suggests the answer to that question is no; UK Co has third party income which is subject to tax in the UK and the US and therefore the double deduction of the third party costs would be negated by UK Co’s dual inclusion income. On repeal of Condition F UK Co will no longer be afforded the same protection and so would be reliant on Non-UK Co being resident in a jurisdiction that has enacted the recommendations of the Action 2 report. Where it is not, economic double taxation will ensue.