In brief

Following the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) in November 2021, almost 200 countries, including Thailand, announced their climate goals and made commitments to tackle climate change. Thailand has pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050 and reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2065. To support the government’s policy in this direction, various government agencies and public organizations, such as the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization, have been actively progressing efforts to realize Thailand’s sustainability goals through various schemes and measures that they are empowered to do under the relevant laws.

The Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) has granted various tax and non-tax privileges to incentivize investors on environmentally friendly projects and businesses. The BOI has accomplished what it can within its competence and the power vested upon it by the law under which it was set up. Important as they are, these tasks are probably among the most clear-cut of duties and obligations of both the public and private sectors. Fundamentally and undoubtedly, the BOI has been successful in attracting investments into Thailand. These investments primarily involve moving business operations to Thailand, such as the production of products and services operations, to enjoy a competitive advantage in the market as a result of the lower costs of production. However, these incentives may not work well this time when it comes to environmental projects related to the COP26 commitments. For example, investors that are most likely to be interested in the carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects are possibly those that currently operate in the petroleum concessions and energy production industry, consisting of only a handful of companies. The incentives for a successful carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) project will be even more complex. The investors that might be interested in CCUS will likely be the same as the companies mentioned above. Moreover, in order for them to see a sensible return and profit in their projected balance sheet, other industrial communities in the possible locations in which their carbon storage utilities will be located must also buy into the projects or they will end up building facilities for no one. These two issues merely deal with only a small part of the problem. Another critical element is the technology that their headquarters must own or be allowed to commercialize. There are also safety measures that the Thai government has to design and implement in a manner that gains the trust of multinational and sophisticated players. On top of this, the reality is that the investment has to be justified with potential investment returns but such profits cannot be projected without potential customers. There would possibly be no customers or only a limited number if the carbon reduction were only managed on a voluntary basis given the relevant costs and potential exposure.

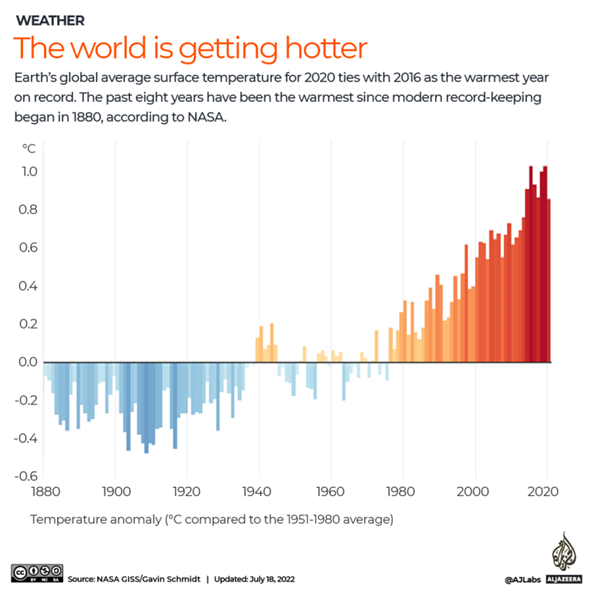

Figure showing statistical data for the rise in global average temperatures.

Source: Aljazeera

Significant projects, such as CCS and CCUS, need more than the BOI’s promotion on paper. The government must consider these projects, including other related COP26 commitments, holistically. Those who have a role to play in making these projects viable and sustainable, such as technology owners, operators of CCS and CCUS in the North Sea, funding/financing and even future customers, should be invited to brainstorming sessions. Government agencies, which might be both drivers and obstacles (due to the existing unfriendly rules and requirements), should come together to identify responsibilities and make sure these projects can materialize and become part of the solutions for Thailand’s commitments. Joint investment from the government side might also be required. It is important that all relevant aspects be taken into consideration when implementing the CCS projects. These include various issues, such as monitoring and measuring CO2 leakage for its entire life-long storage; positive and negative impacts on society and community; long-term impact on the geological structure of the storage site; liability law for damages arising from the CCS; marginal abatement costs of greenhouse gases removal; and advanced technology for CO2 utilization rather than just storage.

In the meantime, the private sector’s voluntary missions should continue to be implemented in parallel. In fact, making such missions mandatory will also be a solution. Such missions might work hand in hand with some financial incentives and tax measures. On tax measures, among various initiatives the government might be working on now, a measure to help prevent carbon leakage by creating a levelled playing field with a similar effect as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism but that could be applicable to different imported products, might also be required to prevent Thailand from falling behind its commitment on climate mitigation.

In summary, management of climate change, which is relevant to Thailand’s commitment under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, requires holistic approaches from both the government and private sector. While patchwork solutions might have been worked reasonably well in the past for some areas, this particular commitment on mitigating the climate change crisis is required to be managed under a tight timeline and increasingly more complex geopolitics that requires concerted and coordinated efforts from all concerned.