This article provides an overview of the global rise in human and labour rights legislation linked to trade measures. In particular, it examines:

- Canada’s efforts to enforce the existing import prohibitions on goods mined or manufactured with forced labour under the Customs Tariff;

- Compliance under the recently passed Bill S-211, Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act and to amend the Customs Tariff which comes into force on January 1, 2024; and

- The need for Canadian businesses to develop compliance measures on the import prohibition under the Customs Tariff, the new reporting requirements under Bill S-211, and the importance of continuing enterprise and supply chain scrutiny.

The Rise of International Human and Labour Rights Legislation Linked to Trade Measures

Over the past decade there has been an accelerating trend toward a global legal regulatory framework requiring entities to comply with international human and labour rights in their own enterprise and supply chains through, what is referred to as “modern slavery” legislation, for example, the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 and California’s Transparency in Supply Chains Act. The legislative reforms resulting from this trend have been principally focused on entities reporting on the measures undertaken to reduce the risk of forced labour in their supply chains. Critics of this “supply chain transparency” legislation point to the lack of accountability and enforcement measures, and therefore the lack of progress, to meaningfully address human and labour rights violations. More recent iterations of modern slavery legislation enacted in France, Australia and the Netherlands has trended toward strengthening compliance requirements and accountability measures for reporting entities. For example, some legislative requirements include positive due diligence measures and increased fines and penal measures for non-compliance.

Canada has lagged behind its allies in implementing modern slavery legislation. Canada’s efforts were initially focused on establishing the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (“CORE”) as a voluntary hybrid measure to address complaints on human and labour rights violations made by Canadian entities in the extractive (mining, oil and gas) and garment sectors.[1] A private member’s bill, which did not immediately attract government support, introduced modern slavery legislation to Parliament in 2018. Four different iterations of this legislation, now with government support, struggled through the Parliamentary law-making process. On May 3, 2023, the House of Commons finally passed Bill S-211, supply chain transparency legislation. In recent statements, the Government committed to “eradicating” forced labour in Canadian supply chains, continuing to legislate on the issue of forced labour, and to strengthening the import ban on goods produced using forced labour by 2024.

To date, the most significant measures to address human and labour rights compliance is the linking of human rights violations, particularly forced and child labour, with trade measures in the US, Canada and Mexico, and the pending legislative reforms in the EU and elsewhere. During the 2018 renegotiation of the NAFTA (now the “USMCA”), Canada and Mexico agreed to introduce laws prohibiting the importation of goods produced with forced labour. Additionally, the USMCA introduced novel new measures in the form of the “Rapid Response Labour Mechanism (“RRLM”) that allows complaints to be brought against companies in significant sectors for violations of freedom of association, collective bargaining and other international labour rights. Pursuant to the RRLM, violations of these rights may result in trade sanctions. In the short time the RRLM has been in place, it has served as a fast and efficient dispute resolution mechanism, proving to be an effective measure to address the violations of human and labour rights.

Coupled with the US repealing the consumptive demand exceptions under the Taft-Hartley Act, which previously exempted imported goods from prohibitions on manufacturing with forced labour, the Biden Administration has embraced the existing provisions to prohibit the importation of goods produced with forced labour using the Customs and Border Protection Agency issuance of Withhold Release Orders . Pursuant to its obligations under the USMCA, Canada amended the Customs Tariff in 2020 to prohibit the importation of goods manufactured or mined with forced labour. To date, Canada’s enforcement record of these provisions has been insignificant. For example, while the US Customs and Border Protection Agency has detained thousands of shipments and is currently enforcing over 50 active withhold release orders and 8 findings issued due to concerns of forced labour, the Canada Border Services Agency (“CBSA“) has reportedly detained only 1 importation. The threshold applied by the CBSA to detain, inspect and prohibit the importation of goods is low – it is based on a “suspicion” of goods being produced with forced labour.

Bill S-211: New Canadian Supply Chain Transparency Legislation

The House of Commons passed Canada’s first supply chain transparency law on May 3, 2023. The legislation establishes a supply chain reporting obligation for business and expands prohibitions under the Customs Tariff legislation. Bill S-211, also known as Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act and to amend the Customs Tariff, (“the Act”) will come into force on January 1, 2024.

Speaking before the House of Commons on March 6, 2023, the Honourable John McKay addressed

the main criticism of the legislation: being supply chain transparency legislation and not due diligence legislation. He stated that Bill S-211’s current reporting thresholds (outlined below) apply to more companies than the due diligence legislation passed in Germany and France and that due diligence legislation “has a limited upside with a massive non-compliance downside, in effect trying to run before crawling or walking”. He indicated that there may be political will in the future to enact due diligence legislation.[2] These comments were recently echoed by the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Labour who noted on April 26, that while Bill S-211 was an important first step in passing effective legislation, the Government “will seek not only to improve upon it, but to go further”.

Reporting Requirements for Business

(a) Scope of the Application of the Act

Businesses that meet the definition of “entity” and engage in prescribed activities are required to file an annual report with the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness (the “Minister”).

A qualifying entity must be engaged in the following activities:

- producing, selling or distributing goods in Canada or elsewhere; or

- importing into Canada goods produced outside of Canada; or

- directly or indirectly controlling an entity that is engaged in one of the two activities listed above.

Additionally, a qualifying entity must either be listed on a Canadian stock exchange, or be a privately-held entity that meets the following criteria (a Canadian nexus and financial threshold):

- a place of business in Canada, does business in Canada or has assets in Canada; and

- Based on its consolidated financial statements, meet at least two of the following conditions for at least one of its two recent financial years:

- has at least $20 million in assets,

- has generated at least $40 million in revenue, and

- employs an average of at least 250 employees.

Importantly, reporting entities are not limited to Canadian incorporated companies. Reporting entities may include non-resident importers that are “doing business in Canada” – a term that is not defined under the Act.

As the asset, revenue and employment thresholds listed above for qualifying entities are quite low, the reporting obligation will be applicable to many medium and large-sized business. The Act provides for the Government of Canada to list additional reporting entities by regulation. Note that the Act is not limited in its application only to Canadian-incorporated corporations.

(b) The Reporting Obligation

The reporting obligation requires reporting entities to file annual reports on or before May 31 annually to the Minister. Reporting entities must outline the policies and procedures implemented in the prior fiscal year to prevent and/or reduce the risk that forced or child labour are used to manufacture goods at any step in a reporting entity’s supply chain.

The Act calls for the establishment of an online public registry of annual reports filed with the Minister. Businesses should consider the potential impact that these reports may have on their goodwill and reputation.

Definitions of Forced and Child Labour

The Act defines forced and child labour. Once passed into law, these definitions will also define the prohibitions under Canada’s Customs Tariff (discussed below).

“Forced labour“ is defined as labour or service provided or offered to be provided by a person under circumstances that:

- could reasonably be expected to cause the person to believe their safety or the safety of a person known to them would be threatened if they failed to provide or offer to provide the labour or service; or

- constitute forced or compulsory labour as defined in article 2 of the Forced Labour Convention , 1930, adopted in Geneva on June 28, 1930.

“Child labour” is defined as labour or services provided or offered to be provided by persons under the age of 18 years and that:

- are provided or offered to be provided in Canada under circumstances that are against Canadian law;

- are provided or offered to be provided under circumstances that are mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous to them;

- interfere with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school, obliging them to leave school prematurely or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work; or

- constitute the worst forms of child labour as defined in article 3 of the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999, adopted at Geneva on June 17, 1999.

These definitions expand upon those provided under the International Labour Conventions, and add important nuances for businesses to consider. For example, the definition of child labour is broad, setting the age at 18, whereas Convention 138, allows for the setting of the minimum age at 15 and includes circumstances where an employer obliges a minor to leave school prematurely. This definition may capture employment contracts which require minor-aged teenagers to work full-time. Canadian businesses should be aware that these types of employment practices implemented by foreign suppliers may increase the risk of their imports being detained by the CBSA.

Enforcement

The Act is penal legislation. An accused charged under section 19(1) of the Act is punishable on summary conviction (a less serious offence than an indictable offence). Failure to comply could result in on-site searches, an order, and, potentially, a summary conviction with a fine of up to $250,000. With respect to on-site searches, the authority extends to searching premises, including residential properties. Except in the case of a search being conducted at a residential property, the search may be “warrantless”.

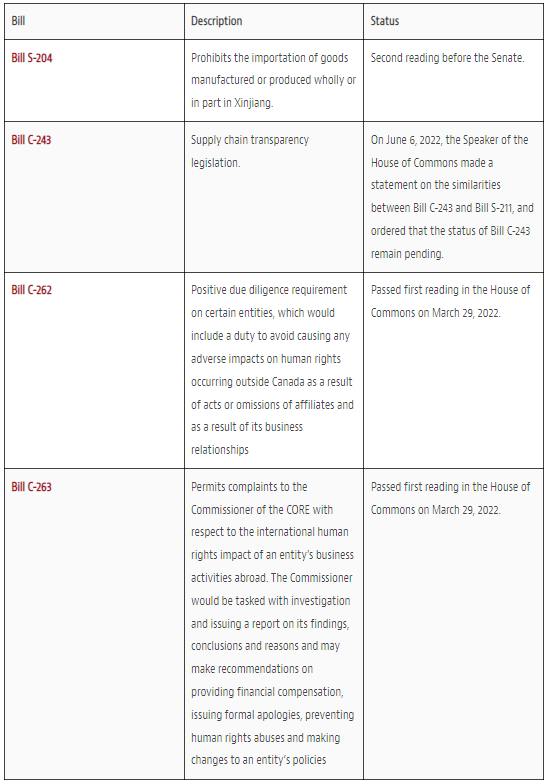

Other Supply-chain Related Bills Before Parliament

There are several other supply-chain focused bills before Parliament:

CBSA Enforcement of Forced and Child Labour Import Prohibition

Article 23.6 of USMCA obligates Canada to prohibit the importation of goods produced, in whole or in part, by forced or compulsory labour. Following the implementation of the USMCA, the Customs Tariff (tariff item No. 9897.00.00) was amended in 2020 to codify Canada’s prohibitions on forced labour. Under the Act, the Customs Tariff and tariff item 9897.00.000will be further amended to prohibit the importation of goods manufactured with child labour, as defined under Bill S-211. This will expand the potential importations that are subject to inspection, and potentially, re-determination by the CBSA.

Despite the initial amendments to the Customs Tariff occurring almost 3 years ago, the CBSA has only detained one shipment on concerns of forced labour. There are no publicly reported cases of the CBSA using the re-determination scheme available under the Customs Act to detain and re-determine the tariff classification of goods manufactured with forced labour. Officials explain that they are attempting the align the Canadian law and regulation with their US counterparts in order to properly implement the measures.

Pursuant to the Customs Act, an importer is required to account for and pay duties and taxes on goods imported into Canada prior to their release. To account for imported goods, an importer must classify goods under the Harmonized System, and select the applicable tariff item. Should the CBSA determine that any goods are produced by forced labour, and are therefore classified under the incorrect tariff item, the CBSA has the authority to re-determine the tariff classification of those goods (to classify those goods under tariff item 9897.00.00) and issue a notice of re-determination to the importer. This re-determination is not final. An importer may appeal to the President of the CBSA to further re-determine the tariff classification. However, this process may result in lengthy proceedings and the possibility of further appeals to the Canadian International Trade Tribunal and/or a judicial review to the Federal Court of Canada.

Practical Considerations for Businesses

The increased focus on human and labour rights violations in the context of international trade underscores the need for businesses to pay close attention to their enterprise and supply chains. While Canada has not yet undertaken robust enforcement of its prohibition on importing goods manufactured with forced labour; with the passage of Bill S-211 and the new USMCA requirements and the growing expectation of consumers, stakeholders and voters, that is sure to change.

Compliance with human and labour rights has quickly risen to the top of the list of legal risk facing companies doing business in North America, the EU and UK. Senior Biden Administration has stated that the US trade agenda is a workers’ rights agenda. That signals the determination of the US to pursue the measures it currently has, and potentially introduce more, to protect labour and human rights.

Canadian businesses can prepare for the upcoming change in the enforcement landscape by considering the following:

- Determining whether they meet the reporting entity requirements under the Act, which comes into force on January 1, 2024. Reporting entities’ first annual reports will be due by May 31, 2024;

- Conducting due diligence on the risk within the enterprise and supply chain for violations of human and labour rights, through the production of a risk assessment or matrix;

- Understanding the reporting and other obligations in the jurisdictions in which you do business and determining whether those various obligations can be aligned into a single report, and whether compliance can be implemented globally;

- Reviewing and aligning internal policies related to human and labour rights, supply chain, procurement and related issues to ensure they are consistent with corporate values and principles;

- Providing robust and meaningful training to those in the enterprise who have oversight or responsibility for the implementation of human and labour rights measures;

- Understanding their supply chain, evaluating, consolidating where necessary and putting in place commercial measures to define accountability; and

- Reviewing Standard Operating Procedures, including third party supplier vetting, to ensure that forced labour concerns are addressed by company policies and meet the requirements outlined in the legislation of their home jurisdiction.

Baker McKenzie is uniquely positioned and qualified to address these global and national risks, wherever they arise, including significant experience in preparing for and responding to detainments of goods by customs officials, drafting and interpreting International Labour Conventions, training c-suite executives and management on international human and labour rights, and conducting audits of supply chains and enterprise risk. The below contacts can answer further questions regarding the risks related to forced labour and other human rights issues.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Articling Student Oscar Ramirez on this post.

[1] The CORE was first tabled by the Government of Canada in 2017. The first Ombudsperson was appointed in 2019. The CORE’s complaint portal was launched in 2021 and it began investigating its first complaint in late 2022.

[2] https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/44-1/house/sitting-164/hansard