In brief

On 6 November 2024, the UK Home Office published its long-awaited guidance on the new failure to prevent fraud offence (“FTPF Offence“). Given the breadth of the FTPF Offence, the new guidance is essential reading for anyone with a role in legal, tax, compliance and/or financial crime in any organisation with a UK nexus.

The FTPF Offence was introduced by the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (ECCTA) and provides that large organisations can be held criminally liable where their employees, agents, subsidiaries, or other “associated persons” commit a specified fraud offence intending to benefit the organisation or its clients. It will be a defence if an organisation can prove that it had in place “reasonable fraud prevention procedures“. All large, incorporated bodies and partnerships are in scope of the FTPF Offence, and it applies both to UK-based organisations and organisations based abroad, where there is a UK nexus.

The guidance offers a detailed overview of the offence itself, as well as an exploration of recommended fraud prevention procedures that companies should have in place if they seek to rely on the “reasonable fraud prevention procedures” defence.

The UK Government has also announced that the FTPF Offence will come into force on 1 September 2025. This gives relevant organisations just under ten months to implement new (or adapt existing) fraud prevention procedures.

Background

The FTPF Offence was introduced following long-standing efforts to enhance the UK’s economic crime enforcement framework, as detailed in a Law Commission paper published in June 2022. It was finally introduced as part of the ECCTA in October 2023 (albeit, it will not come into force until 1 September 2025).

The legislation aims to increase the ability of UK law enforcement agencies to hold large corporations to account for wrongdoing by those associated with them, including their employees. Additionally, it is hoped that the FTPF Offence will motivate organisations to implement, or revamp, fraud prevention procedures to minimise the risk of wrongdoing in the first place.

The FTPF Offence

Under S. 199 of the ECCTA, the FTPF Offence will have been committed by a large organisation if an employee, agent, subsidiary or other “associated person” commits a specified fraud offence intending to benefit the organisation or its clients. It is not required that the organisation’s management knew about or directed the fraud. Crucially, an organisation will not be liable where it is determined that the organisation itself was, or was intended to be, the victim of the fraud.

1. What are the large organisations

The FTPF Offence applies to all organisations incorporated or formed by any means. This includes both companies and partnerships, as well as certain charitable organisations. In order to fall in scope of the FTPF Offence, such an organisation must also meet two out of three of the following criteria:

- More than 250 employees

- More than GBP 36 million turnover

- More than GBP 18 million in total assets

The above criteria apply to whole organisations including subsidiaries.

2. Who is an associated person?

For the purposes of the FTPF Offence, employees, agents and subsidiaries are automatically considered to be an “associated person“. A person providing services for or on behalf of the large organisation will also be considered an associated person for the purposes of the FTPF Offence. The guidance specifies that organisations that are too small to be considered a “large organisation” under the criteria mentioned above may still be considered an associated person of a large organisation, capable of committing a base fraud offence. Similarly, employees of a subsidiary of a parent company that is a large organisation can bring the parent company within the scope of the offence if the employee commits a fraud intended to benefit the parent company.

The definition of “associated person” for the purposes of the FTPF Offence is broadly similar to the definition included in the UK Bribery Act 2010 (the “UKBA“) and the Criminal Finances Act 2017 (the “CFA“). However, subtle differences exist and so care should be taken to ensure that a fresh review is conducted into which individuals and companies may be associated with the organisation for the purposes of the FTPF Offence.

The guidance offers helpful clarification that persons providing services to an organisation do not fall within the scope of the associated person definition. This means that the conduct of parties such as an organisation’s external lawyers or accountants who are providing services to rather than for or on behalf of an organisation will not attract corporate criminal liability for the relevant organisation.

3. What are the base fraud offences?

The base fraud offences which can attract corporate liability are listed in Schedule 13 of the ECCTA. They are:

- Cheating the public revenue;

- Fraud by false representation;

- Fraud by failing to disclose information;

- Fraud by abuse of position;

- Participation in a fraudulent business;

- Obtaining services dishonestly;

- False accounting;

- False statements by company directors;

- Fraudulent trading;

- Fraud, uttering, embezzlement (in Scotland); and

- Aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the commission or any of the above.

Money laundering offences under the UK Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 are not included in the list.

It is important to note that the common law offence of cheating the public revenue is very wide and includes dishonest acts or omissions that are intended to prejudice HMRC. There is therefore a large overlap between this and the corporate offences of failing to prevent the criminal facilitation of tax evasion under the CFA with the possibility that an offence of failing to prevent criminal facilitation of tax evasion may also constitute a FTPF Offence.

It is not a requirement of the FTPF Offence that the individual who committed the base fraud offence is convicted. If the associated person has not been convicted, the prosecution of the relevant organisation must prove, to a criminal standard, that they did commit the base fraud offence.

4. What does “intending to benefit” mean?

The new guidance clarifies that a relevant organisation or its client need not actually receive any benefit for the offence to have occurred – it is sufficient that they were an intended beneficiary. Additionally, benefitting the relevant organisation or its client need not be the sole intent behind the fraud – even if an associated person is primarily motivated to commit fraud to benefit themselves, if the relevant organisation or its client also benefits this would still be in scope of the offence.

5. What territorial restrictions apply?

In order to fall within scope of the FTPF Offence, the base fraud must have a UK nexus. This means that the base fraud must have taken place (at least in part) in the UK, or the resultant gain or loss occurred in the UK. As a result, a relevant organisation based outside the UK may be prosecuted if an employee, agent, subsidiary or other associated person commits fraud in the UK, or targets UK-based victims.

The FTPF Offence will not apply to a UK-based organisation where an employee, agent, subsidiary or other associated person commits fraud with no UK nexus.

The FTPF Offence arguably has wider territorial reach than the UKBA. Under the UKBA, the corporate offence of failure to prevent bribery applies to any relevant commercial organisation that is incorporated or formed in the UK or carries out at least part of its business in the UK. This means an organisation may attract corporate criminal liability under the UKBA even where no part of the bribery or the resultant gain occurs in the UK.

Similarly, the FTPF Offence arguably has wider territorial reach than the failure to prevent criminal facilitation of tax evasion offences under the CFA. Where evasion of a UK tax is concerned, an organisation may be held criminally liable regardless of where they are based. Where evasion of foreign tax is concerned, there must be a UK nexus, i.e., the relevant organisation must (i) be incorporated or formed in the UK; (ii) carry out at least part of its business in the UK in order to attract criminal liability; or (iii) have an associated person who is located in the UK at the time they commit the criminal act that facilitates the evasion of overseas tax. (There must also be so-called “dual criminality”, i.e., both the UK and the overseas jurisdiction must have equivalent offences for both the tax evasion and criminal facilitation).

As mentioned above, an organisation may be liable under the FTPF Offence without any ties to the UK, if the base fraud offence has a UK nexus.

6. How will the FTPF Offence be prosecuted and enforced?

Interestingly, the guidance states that the willingness of a relevant organisation to participate in an ECCTA investigation will be taken into account by authorities when deciding whether or not to commence criminal proceedings. It further states that this cooperation will be considered when determining if an organisation is offered the option of a Deferred Prosecution Agreement.

If a relevant organisation is successfully convicted on indictment, or on summary conviction, it will be subject to a fine. The sentencing guidelines dictate that the level of fine imposed will be impacted by several factors, but the level of penalty could be very significant. Fines imposed by UK courts on organisations for compliance breaches in recent years have run into the tens and hundreds of millions of pounds and there is no reason to think that the enforcement of the FTPF Offence will be any different.

Reasonable fraud prevention procedures

Organisations will have a defence to the FTPF Offence if they are able to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that they have implemented “reasonable fraud prevention procedures“.

The guidance aims to help organisations evaluate what will amount to “reasonable fraud prevention procedures”. To that end, it describes six general fraud prevention principles that courts will consider when determining whether an organisation had reasonable fraud prevention measures in place:

- Top level commitment

- Risk assessment

- Proportionate risk-based prevention procedures

- Due diligence

- Communication (including training)

- Monitoring and review

These principles echo the six principles outlined in the Ministry of Justice guidance issued in relation to the adequate procedures defence under the UKBA, and the subsequent HMRC guidance in relation to the offences of failure to prevent the criminal facilitation of tax evasion under the CFA. However, the guidance contains additional detail for the purposes of the FTPF Offence.

While adherence to the above principles and engagement with procedures recommended in the guidance will help organisations to prove that they had reasonable fraud prevention procedures in place, the guidance is clear that it is advisory, rather than binding. The onus will be on organisations to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that the fraud prevention measures they had in place were reasonable considering the context and the facts at hand.

1. Top level commitment

The guidance stresses that senior management should be leaders in an organisation’s fraud-prevention efforts. It highlights the following as likely aspects of the roles that senior management should take on in relation to fraud prevention:

- Communicating and endorsing the organisation’s fraud prevention stance.

- Ensuring there is clear governance across the organisation relating to fraud prevention.

- Committing to training and resourcing.

- Leading by example and fostering an open culture.

2. Risk assessment

The guidance puts forward that a relevant organisation should assess its potential exposure to the risk of associated persons committing fraud intended to benefit the organisation or its clients. This assessment must be dynamic and subject to regular review.

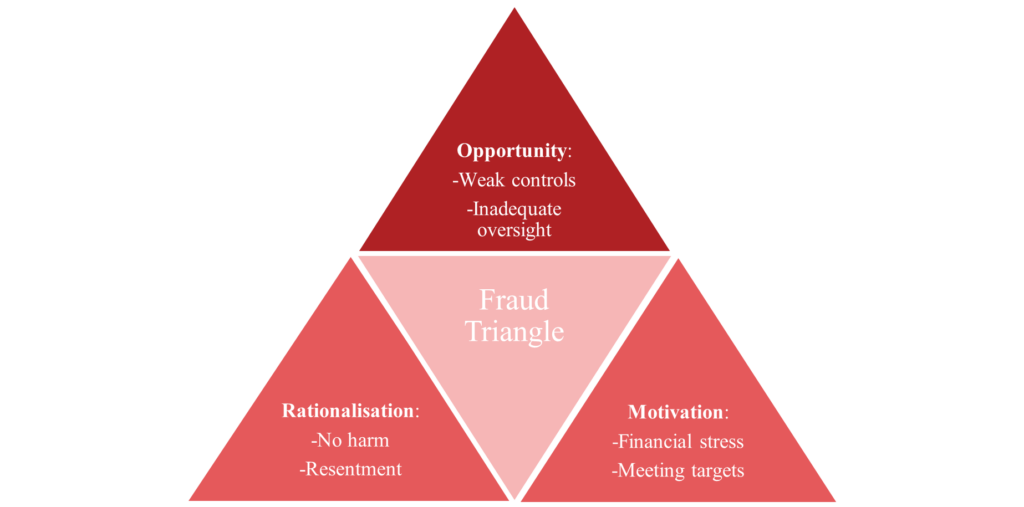

It is suggested within the guidance that organisations use the “fraud triangle” when assessing these risks. While risk assessment was a principle under previous guidance to the UKBA and the failure to prevent the facilitation of tax evasion offences, the focus on analysing opportunity, motive, and rationalisation under this principle is a new addition for the purposes of the FTPF Offence.

3. Proportionate risk-based prevention procedures

The guidance highlights that the procedures put in place to prevent fraud and documented in a fraud prevention plan should be proportionate both to the risk identified during the course of the risk assessment, and to the nature, scale, and complexity of the organisation’s activities.

While the guidance recognises that it may sometimes be reasonable not to introduce fraud prevention measures in response to a particular risk, any such decision and who made it should be clearly documented and subject to regular review.

The guidance acknowledges that many organisations within scope of the FTPF Offence are already subject to other regulatory regimes which may address potential fraud (e.g. regulated UK financial institutions), and states that duplication of procedures to prevent fraud is not necessary. However, it offers a strong reminder that compliance with other regulations does not automatically give rise to a “reasonable procedures” defence.

4. Due diligence

The guidance recommends that organisations take a proportionate and risk-based approach to due diligence conducted on associated persons and in relation to mergers or acquisitions. While relevant organisations may already have mechanisms in place to conduct due diligence, it is additionally recommended that organisations consider whether they are sufficient to address the risks created by the FTPF Offence.

5. Communication (including training)

It is key that any fraud prevention procedures put in place are clearly communicated at all levels within the relevant organisation, and that training on fraud prevention is provided and maintained. The guidance offers recommendations and strategies to communicate effectively on the subject, including that organisations may wish to internally publicise the outcome of fraud investigations and the sanctions imposed.

6. Monitoring and review

The guidance stresses the importance of continued monitoring and review of fraud detection and prevention procedures, including making appropriate improvements where necessary. It also places considerable emphasis on the fact that investigations into suspected fraud must be independent, appropriately scoped and properly resourced. The guidance encourages organisations to self-reflect on their fraud prevention strategy by considering questions including whether data analytics tools are being used effectively, whether investigation arrangements are adequate, and whether employees are engaging with fraud prevention training programmes. A relevant organisation must also be prepared to enhance procedures based on lessons learned from previous investigations, whistleblowing incidents, and developments within its own sector.

Conclusion

The FTPF Offence represents a shift in the UK corporate crime landscape as, for the first time, organisations can be held liable for failing to prevent fraud committed by those associated with them. Like the previous “failure to prevent” type offences in the UK (including Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act 2011), the FTPF Offence has very broad jurisdictional reach.

The guidance should be carefully reviewed by anyone within an organisation with an interest in this area. Action should be taken now to ensure that, before 1 September 2025, organisations have in place anti-fraud procedures which reflect the UK Government’s new guidance. For most organisations, the starting point will likely be a thorough and detailed risk assessment, with a view to leveraging any existing processes that are already in place to meet their obligations under the UK Bribery Act 2010 as well as the corporate offences of failing to prevent the criminal facilitation of tax evasion.

The guidance has a few key messages that organisations should carefully consider:

- Those in senior positions in relevant organisations bear the responsibility for building a robust, top-down approach to fraud prevention. Clear communication and thorough training are paramount.

- Organisations should complete a thorough fraud risk assessment and review of their existing fraud prevention measures in order to ensure they are fit for purpose by 1 September 2025. As the guidance highlights frequently, showing that an organisation complies with other regulatory regimes is insufficient to show reasonable fraud prevention procedures for the purposes of the FTPF Offence.

- Once appropriate fraud prevention procedures are in place, including but not limited to risk assessments and due diligence, they must be subject to regular and thorough review to ensure that they remain up to date.

An on-demand webinar by Baker McKenzie is available on this topic: Economic Crime Update: Introduction to the Failure to Prevent Fraud Offence and Corporate Criminal Liability Reforms to explain the FTPF Offence in more detail. If you would like any further detail on the new FTPF Offence or the guidance please contact your usual Baker McKenzie contact who will put you in touch with the relevant members of the team.