In 2015, Vicinity Centres—a leading Australian real estate group with holdings that include Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building, along with iconic buildings in other major cities—began a process of identifying their risks and opportunities in light of climate change. Then, in early 2017, Cyclone Debbie struck off the coast of Queensland, devastating communities and damaging one of Vicinity’s key assets—the Whitsunday Plaza.1

Vicinity chose to use this event as an opportunity. With assistance from Aecom, it integrated lessons learned from that disaster into the climate resilience checklist it had been developing to identify location and asset‑specific risks, resilience measures already in place and opportunities to further strengthen their approach to climate change.

By 2020, the company will have completed these assessments for its entire portfolio, giving it a much better understanding of how climate change will impact its businesses, and how it can build itself into a resilient organisation for the future.

Vicinity is in good company. Leading businesses in Australia and across the globe are now

adopting a framework for identifying and quantifying the risks and opportunities presented

by climate change. Stockland, another AECOM client, has become an industry leader in this

field. Not only does it disclose detailed analyses of its climate risks and opportunities, but these disclosures tell a good financial story: since 2006, the company has reduced 40 per cent of emissions across its retail and office/business park portfolios, and has saved more than $78 million in avoided electricity costs.2

We are now at the point where the business case and the legal impetus for climate change

disclosures have aligned.

The following discussion paper provides a brief consideration of these questions. Because the impacts of climate change will be specific not just to each industry, but to each company, this paper is an overview, intended as a primer for business leaders who wish to begin the process of designing and implementing a framework that will allow for the establishment of resilient businesses while also protecting directors from potential liability with respect to their duties under Australian companies law.

For those who wish to engage in a more tailored exploration of these issues, Baker McKenzie, AECOM and Ndevr Environmental are available to conduct onsite client workshops. Please contact us should you wish to arrange a workshop for your organisation.

It’s Time For Companies To Get Serious About Disclosing Climate Risks And Opportunities

Following last November’s boardroom briefings held by Baker McKenzie, Ndevr Environmental and AECOM on the recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), we are pleased to provide you with the following discussion paper on how business leaders can meet their legal obligations to assess and disclose the financial risks and opportunities linked to climate change.

Since we held those briefings, the landscape relating to climate risk and opportunities has continued to change rapidly, with several significant developments:

- In late November, the Australian Labor Party announced an energy platform that would see massive new investments in renewable energy, along with more aggressive targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions on a shorter timeframe than current policy would indicate, and even faster than Australia’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.3

- In January, the Federal Court of Australia said that a case against a superannuation fund for failing to disclose climate risk, including failure to comply with the TCFD recommendations, “appears to raise a socially significant issue about the role of superannuation trusts and trustees in the current public controversy about climate change”.4

- In early February, the NSW Land and Environment Court delivered a landmark decision on new mines, in which the court took into consideration the proposed mine’s expected greenhouse gas emissions, including scopes 1, 2, and 3, and assessed these emissions against the framework of the remaining “carbon budget” that sets out how much more carbon dioxide can be emitted into the atmosphere while still limiting warming to less that 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. In assessing the supposed economic benefits of the mine, the court appeared to favourably view evidence that demand for new coal could decline as countries shift to clean and renewable sources of energy.5

- In the same month, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) and the Australian Accounting Standards Board released guidelines that included for the first time a clause requiring directors of listed companies to follow the recommendations of the TCFD, and the UNPRI (Principles for Responsible Investment) reported that TCFD-based reporting will become mandatory for PRI signatories in 2020.6

- Also in February, Glencore—Australia’s largest coal miner—announced that it will cap future coal production at this year’s levels.7

- In March, the Reserve Bank of Australia8 joined the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority9 and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission10 in recognising climate change as a material economic risk to the Australian economy, and strongly endorsing “the need for businesses, including those in the financial sector, to implement the recommendations of the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures.”

In this rapidly moving space, it is paramount that corporate directors and officers inform

themselves of what is required under Australian law in relation to disclosing climate risk. Doing so requires, in turn, a practical working knowledge of the leading framework for thinking about, measuring, and reporting such risk—that is, the 2017 recommendations published by the TCFD at the request of the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors.11

Organisations can reduce their vulnerability to climate change related risks by understanding the climate impacts on their operations, assets, and customers, and by strengthening their governance to minimise these impacts, and to adapt. Effective management of climate change risks and opportunities will help meet the board’s obligation to generate value for the company’s stakeholders.

In the short time since those recommendations were published, they have made a significant impact in the approach to assessing, managing and reporting risk by leading global and ASX companies.12 By September 2018, 513 companies had signed on as “supporters” of the initiative. The recommendations have also spurred a broader conversation about how businesses will be affected by climate change; it’s a shift in lens from even a few years ago, when the focus was mostly on how the climate was being affected by business.

Regulators Are Watching Companies’ Climate Disclosures

Yet, recent research confirms what we are hearing from the market: the majority of companies are still falling short of their legal obligations with respect to disclosure of climate risks. In September 2018, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) published the results of a study it had undertaken to determine whether companies were, as ASIC put it, “complying with the law” that requires them to disclose material risk, which may include climate change. ASIC reviewed climate risk disclosures by 60 companies in the ASX 300, 25 recent initial public offering prospectuses, and analysed 15,000 other annual reports, and found that while the majority of companies appeared to have considered climate risk, their disclosures fell far short of what would be desired. ASIC recommended that companies: consider climate risk; develop and maintain strong and effective corporate governance; comply with the law (section 299A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)); and disclose useful information to investors.13 In its report, ASIC also noted that the Australian government has welcomed the TCFD report, and recommended that “listed companies with material exposure to climate risk consider reporting under the TCFD framework.” 14

In our view, it is noteworthy that regulators have demonstrated a willingness to proactively initiate these kinds of investigations, particularly following the Royal Commission into the banking industry, which has left regulators emboldened and newly assertive.

Despite a growing awareness that companies must take climate change into account, there is a substantial knowledge and compliance gap when it comes to understanding what risks and opportunities need to be assessed; how to assess and manage them; where to disclose them; and the consequences associated with failure to manage and disclose.

What are the TCFD Recommendations?

The recommendations are contained within the 74-page report published by the TCFD in 2017.

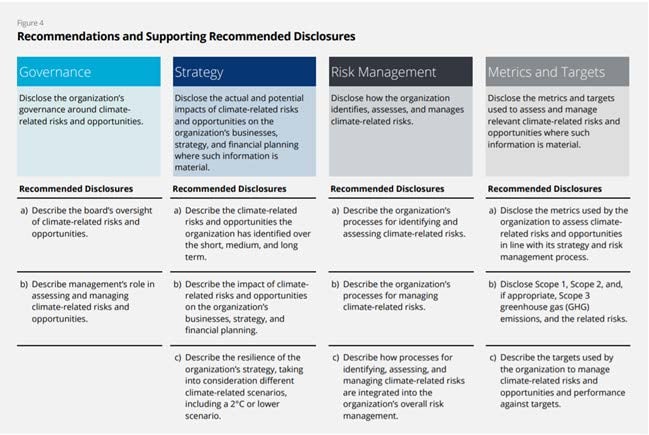

They are broken into four categories:

- Governance;

- Strategy;

- Risk management; and

- Metrics and targets.

Each of these categories, in turn, is tied to specific recommended disclosures as set out in the diagram on page 5.15

The report also contains recommendations on where these disclosures should be made, generally concluding that companies should comply with all applicable legal requirements, but should also ideally make these disclosures in publicly available reports, such as annual reports, or where that is not applicable, in reports to investors.16 The TCFD recommends that the disclosures be specific to the company, not general in nature; in its 2018 review of disclosures, the TCFD found that general disclosures were not “decision-useful” and also encouraged companies to report climate risks in one place, not in a “fragmented” manner where information was disclosed in different ways, and to different degrees, in different reports that could not be easily pieced to together and assessed by potential investors or regulators. The TCFD developed seven principles for disclosure, which hinge on high-quality, objective data.

Implicit in all of these recommendations is the assumption that boards and companies know how to identify, assess and manage climate risk and opportunities. In reality, this is neither a simple nor obvious exercise. However, through skillful use of scenario analysis and physical risk assessment, it is likely that directors can simultaneously satisfy their legal obligations, substantially enhance their understanding of how climate change will impact their business—both in terms of challenges and opportunities—and enhance their strategies to address those impacts.

How Does the TCFD Conceptualise “Risk and Opportunity”

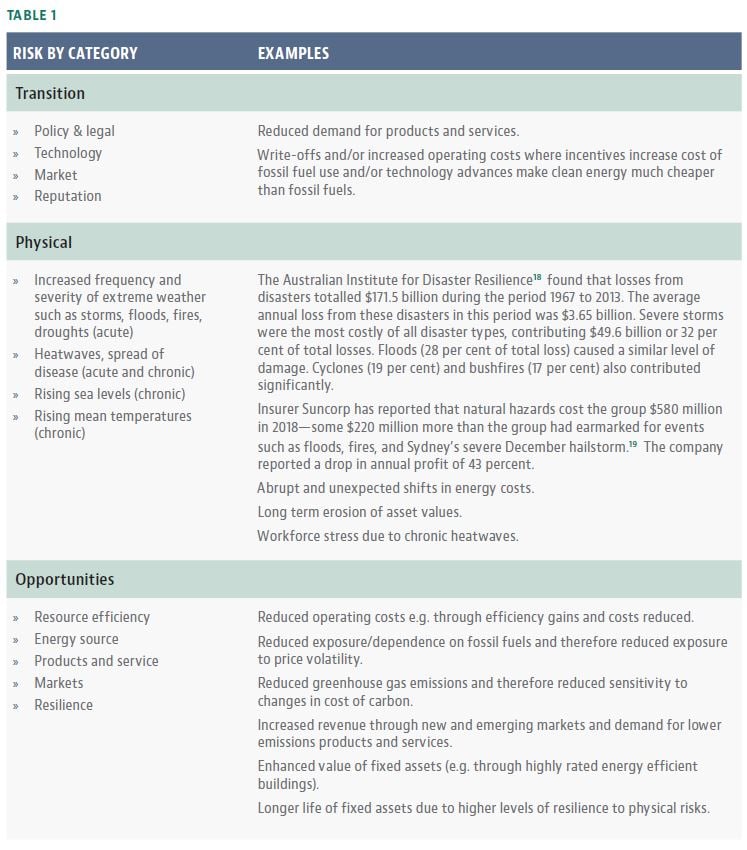

The TCFD divided climate risks and opportunities into two buckets: physical risks arising from climate change, which can be acute (such as floods, fires, storms, heatwaves etc) or chronic (changes to rainfall patterns, increased heat stress on workforces, etc.); and transition risks and opportunities arising from the rapid transition to a low-carbon economy.

Over the past year, leaders in the corporate climate risk space have emphasised that we are now seeing transition risk and physical risk occur simultaneously, with the pace of climate change occurring faster than predicted, e.g., increased frequency and intensity of catastrophic fire, storms, floods and droughts across the globe, as well as an accelerated trend for countries and subnational players to take action to curb greenhouse gas emissions while supporting clean energy uptake.

Below is an abbreviated version of the table of climate risks and opportunities set out in the TCFD report. 17

Scenario Analysis ‒ The Best Solution Available

To identify these risks and opportunities, the TCFD urges companies to use scenario analysis, because “the efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change are without historical precedent.”20 The nature of scenario planning—which constructs several versions of a possible future and then tests a company’s resilience against each of those scenarios—best lends itself to planning in the context of multiple levels of uncertainty.21

On the point of uncertainty, until recently, discussions of climate risk tended to include the effects of climate change as a point of uncertainty. It is crucial for business leaders to understand that there is no longer any serious doubt remaining around whether the predicted results of climate change will occur.22 While the question of precisely when these phenomena will occur does remain, scientists agree that the expected effects are occurring sooner than predicted. For this reason, the TCFD stresses that scenarios should be based on the best available science relating to climate change and its impacts on the environment.

The TCFD distilled five reasons for preferring a scenario analysis approach to climate disclosures:

- Scenario analysis, through articulating and exploring a range of possible futures, is best suited to planning in high-uncertainty contexts. This is especially true of climate change where, while the occurrence of both physical and transition risks is almost certain, there is great uncertainty as to the specific nature and timing of how those risks will unfold.

- Scenario analysis can enhance organisations’ strategic conversations about the future.

- Scenario analysis can lead to more robust strategies.

- Scenario analysis can help organisations identify indicators to monitor and map those indicators to their various strategies, leading to greater adaptability and resilience.

- Scenario analysis can assist investors in understanding the robustness of organisations’ strategies and financial plans in relation to climate change risk.

The recommendations say that organisations should develop “a set of scenarios (not just one) that covers a reasonable variety of future outcomes, both favourable and unfavourable. In this regard, the Task Force recommends organisations use a 2 degree or lower scenario in addition to two or three other scenarios most relevant to their circumstances, such as scenarios related to Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), physical climate-related scenarios, or other challenging scenarios.”23

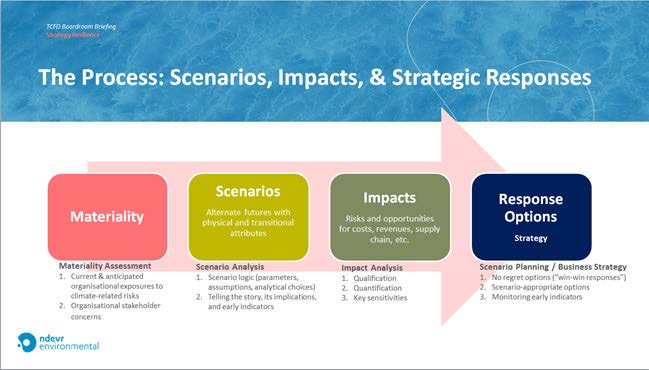

How to Develop and Use Scenario Analysis

As the TFCD notes, to be useful, scenario analysis must be detailed and specific to the particular company that is undertaking the task. The physical risks of climate change, for instance, will be specific to each company or entity, and will likely have uneven business impacts on different locations and industries.

In general terms, the process around scenario planning can be seen in the following diagram.

Depending on the particular company, the exercise may require varying levels of data.

By way of example, companies may need to identify, measure, assess and disclose:

Transaction Risks

- Increasing price placed on greenhouse gas emissions and/or policies that require greater offsets from emitters.

- A fundamental step in assessing climate risk is to understand the current and projected emissions resulting from direct and indirect operations.

- Scenario analysis can generate clear and actionable data that can be used to begin specific strategic planning with respect to managing and mitigating emissions, along with providing a foundation for predicting costs of offsetting in light of those emissions strategies.

Physical Risks

- More frequent and severe cyclones (acute risk)

- Assessment of which assets are particularly vulnerable to storms, taking into account likely damage to buildings, infrastructure, and the need to adapt for severe weather, e.g., through use of different construction methods and materials, and the availability of back-up sources of power.

- Sea level rise (chronic risk)

- Assessment of vulnerability of physical assets, e.g., identification of how many days per year particular buildings, sites, or infrastructure could be inundated, and the associated costs/losses.

Knowing which questions to ask at the outset will enable a company to prepare to engage in a scenario analysis process. All of this requires assistance from those with expertise in the law and science surrounding climate change.

For companies that seek to understand the impacts of climate change on their organisations and are at an early stage of maturity when it comes to managing climate risk it is best to begin by understanding the physical impacts of climate change.

The TCFD recommendations note that is important to explore a range of possible future climate scenarios when assessing the implications of climate change on an organisation, and there is considerable variability between the four emission pathways (RCPs) identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). When considering how best to understand physical climate risks, an appropriate scenario is RCP8.5. This is the most challenging scenario in terms of physical risk, with limited drivers to curb the continued use of fossil fuels and a projected increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme events. Over the past decade, observed emissions have been tracking close to this most extreme emission scenario. In addition, over the next 15 years this trajectory is unlikely to change significantly, suggesting that the most extreme emissions scenario is more likely to occur in the short term.

RCP 2.6, conversely, can be used to understand transition risks. RCP2.6 represents the pathway most closely aligned with delivering against the Paris Agreement targets. It represents the most disruptive scenario with regards to transitioning to a low carbon economy led by policy drivers, market transformation, legal risk and technological change and is considered to be the only scenario likely to limit warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, as acknowledged by the TCFD.24

Building Resilience to Physical Climate Risks

In September 2018, ASIC released a report that examined the 2017 annual reports of 60 companies in the ASX 300, of which just 17 per cent disclosed climate change as a “material risk”. “In some cases, the review found climate-risk disclosures to be far too general and of limited use to investors. Outside of companies in the ASX 200, there was very limited climate risk disclosure by listed companies,” ASIC said.25

By understanding where a company’s vulnerabilities lie both in terms of physical and transition risks, leaders are better able to bolster their ability to react to those challenges, e.g., by adapting buildings, infrastructure and supply chains to better withstand extreme weather events, and to diversify investment portfolios in response to anticipated regulatory and legal changes to energy policy.

Adaptation in the context of climate change can involve adjustments to climate change effects and impacts. Done well, adaptation can lead to climate resilience, which is the capacity of organisations to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of climate-related chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.

Resilient companies are also looking to adapt their products and services to survive and thrive in a low-carbon world. The more resilient a company, the lower its climate risks.

While there is an understandable tendency to focus on the threat posed by climate change,

business leaders have also recognised the inherent opportunities presented in the process of climate adaptation and resilience, both in terms of how companies can improve internal and external performance. At a minimum, the process can allow leaders to identify areas of existing inefficiencies with respect to energy consumption, and to realise cost-savings through improved efficiency and/or swapping to alternative energy sources. But companies can also use the framing of adaptation and resilience to develop new products, services and markets.

It is important to take an integrated approach to identifying and implementing climate change adaptation and mitigation measures. An integrated approach has several benefits. It reduces the risk of implementing adaptation measures that exacerbate the root problem by increasing carbon emissions, for example building a concrete flood wall to protect against increased risk of flooding. It also opens opportunities for efficiencies, i.e., measures that both reduce carbon emissions and build resilience to extreme weather, for example using a nature-based solution such as mangroves as flood protection.

Finally, an integrated approach helps protect investments in adaptation from becoming

worthless. Coral reefs are a case in point: the recent IPCC Report on 1.5 degrees Celsius of

warming, confirms that the worlds’ coral reefs will not survive 2 degrees of warming and will suffer extensive damage with 1.5 degrees of warming. Any meaningful approach to help coral reefs adapt to climate change must involve climate mitigation.

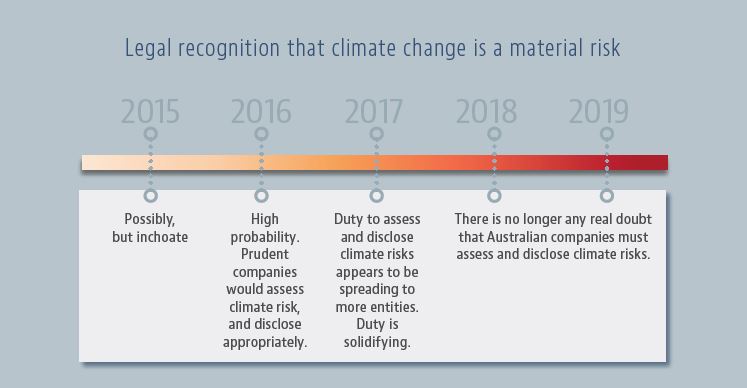

Legal Consequences for Failing to Disclose Climate Risk

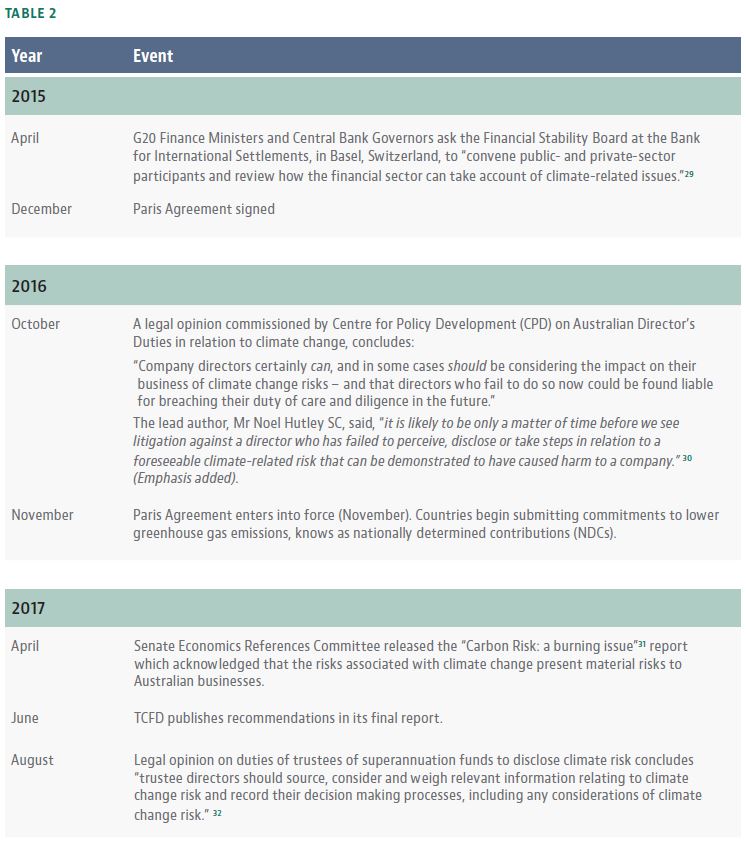

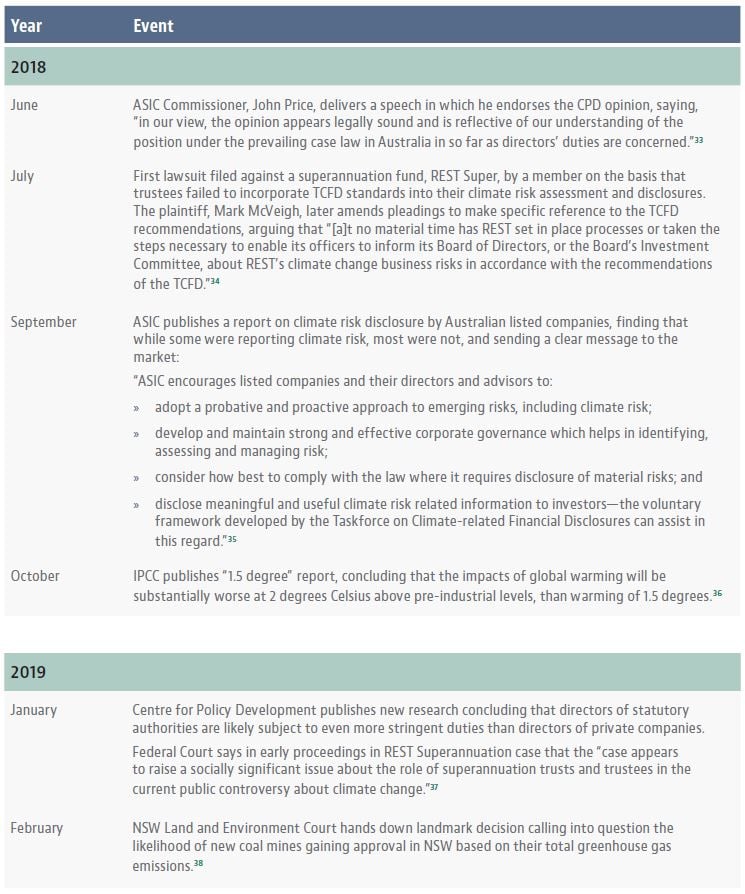

Like the climate itself, the law relating to climate change is shifting rapidly. As Table 2 shows, in the past four years alone, the duty of Australian company directors to disclose climate risks—certainly directors of publicly listed companies—has crystallised from a somewhat amorphous set of recommendations into a clear legal obligation, with an understanding that “Australia’s current corporate disclosure legislation is compatible with the adoption of the TCFD recommendations.”26 This duty is already starting to spread to decision-makers and trustees in other types of institutions.

Indeed, litigants in Australia and elsewhere have wasted no time in using these newly solidified laws as a springboard to sue those who appear to have failed to fulfill their disclosure

obligations. 27

For directors, the consequences of failing to adequately assess and disclose climate risk are potentially severe, including personal liability as well as the chance that they could be prohibited from managing a company.28

As Emma Herd, CEO of the Investor Group for Climate Change, said recently, in confronting these risks, “the best approach is to have rock solid internal governance around climate change.”

Together, Baker McKenzie, Ndevr Environmental and AECOM bring to the table leading global experience and expertise in assessing and disclosing climate risk. Please contact us should you wish to arrange an on-site workshop to discuss how to arrange and conduct scenario analysis in order to meet your legal and other obligations.

References

[1] https://wlpdf.weblink.com.au/pdf/SGP/01952841.pdf.

[2] http://sustainability.vicinity.com.au/improving-ourenvironment/ climate-resilience/learn-more/.

[3] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-11-22/bill-shortenlabor-to-revive-national-energy-guarantee/10521468.

[4] McVeigh v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 14.

[5] https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2019/02/no-more-coalmines.

[6] ASX Corporate Governance Council, 2019. Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations, 4th Edition. Available online: https://www.asx.com.au/documents/asx-compliance/cgc-principles-andrecommendations-fourth-edn.pdf.

[7] https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/australia-s-biggest-coal-miner-moves-to-cap-globaloutput-20190220-p50z4r.html.

[8] Debelle, G., 2019. Speech: Climate Change and the Economy. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2019/sp-dg-2019-03-12.html#fn5.

[9] Summerhayes, G., 2017. The weight of money: A business case for climate risk resilience. Available online: https://www.apra.gov.au/media-centre/speeches/weightmoney-business-case-climate-risk-resilience.

[10] Price, J., 2018. Disclosing climate risk. Available online:https://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/corporategovernance/corporate-governance-articles/disclosingclimate-risk/.

[11] TCFD, “Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Status Report”, (2018), p 1.

[12] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/tcfd-supporters/.

[13] https://download.asic.gov.au/media/4871341/rep593-published-20-september-2018.pdf.

[14] https://download.asic.gov.au/media/4871341/rep593-published-20-september-2018.pdf p 12.

[15] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, (2017), p 14.

[16] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, (2017), p 33.

[17] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, (2017), pp10-11.

[18] Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience, 2018. Updating the costs of disasters in Australia. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, April 2018 edition. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/ajem-apr-2018-updating-the-costs-ofdisasters-in-australia/.

[19] https://www.insurancenews.com.au/daily/sydney-stormregulatory-costs-sink-suncorp-earnings.

[20] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force

[21] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, (2017), p 25.

[22] https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/.

[23] TCFD, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, (2017), p 27.

[24] Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Technical Supplement: The Use of Scenario Analysis in Disclosure of Climate-related Risks and Opportunities. June 2017.

[25] Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2018. 18-273MR ASIC reports on climate risk disclosure by Australia’s listed companies. Available online: https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/find-a-mediarelease/2018-releases/18-273mr-asic-reports-on-climaterisk-disclosure-by-australia-s-listed-companies.

[26] https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=4396, p 17.

[27] Preston, B., “Mapping Climate Litigation” (2018) 92 ALJ 774.

[28] https://asic.gov.au/for-business/your-business/toolsand-resources-for-business-names-and-companies/asicguide-for-small-business-directors/directors-liabilitieswhen-

things-go-wrong/.

[29] TCFD, “Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Status Report”, (2018), p 1.

[30] https://www.envirojustice.org.au/rest-case-to-setclimate-risk-precedent/,

https://cpd.org.au/2016/10/directorsduties/.

[31] https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Economics/

Carbonriskdisclosure45/Report.

[32] https://www.envirojustice.org.au/sites/default/files/files/20170615%20Superannuation%

20Trustee%20Duties%20and%20Climate%20Change%20(Hutley%20%26%20Mack).pdf.

[33] https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/speeches/climate-change/.

[34] https://www.envirojustice.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/180921-Amended-Concise-Statement-STAMPED.pdf.

[35] https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/find-amedia-release/2018-releases/18-273mr-asic-reports-onclimate-risk-disclosure-by-australia-s-listed-companies/.

[36] https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/.

[37] McVeigh v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 14.

[38] https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2019/02/no-more-coalmines.