One of the most contentious issues in legal procedures in Indonesian competition law

is how to ensure due process of law in the KPPU examination process. There have been many complaints that the current practice is lacking in basic due to process guarantee. In particular, there were complaints that business actors were not being given sufficient access to the KPPU’s case files to enable them to mount an effective defense. Another frequent complaint is that business actors often do not have sufficient time to submit supporting evidence or witnesses and to cross examine the KPPU’s witnesses.

Another long standing issue in legal procedures is standard of proof. KPPU cases are often lacking in hard evidence in the form of direct evidence of anti-competitive behavior. In many cases, the KPPU relies on indirect evidence such economic analysis as grounds for its decision. The issue is that kind of evidence is often unconvincing as it is subject to interpretation. For instance, the KPPU cites price parallelism combined with high market concentration as evidence of cartel behavior. The same set of facts can be read as evidence of a highly-competitive market. The draft amendment was supposed to help resolve this issue by giving KPPU additional measures to gather direct evidence, e.g., through a leniency mechanism that would enable whistleblowers to gain immunity in exchange for giving evidence.

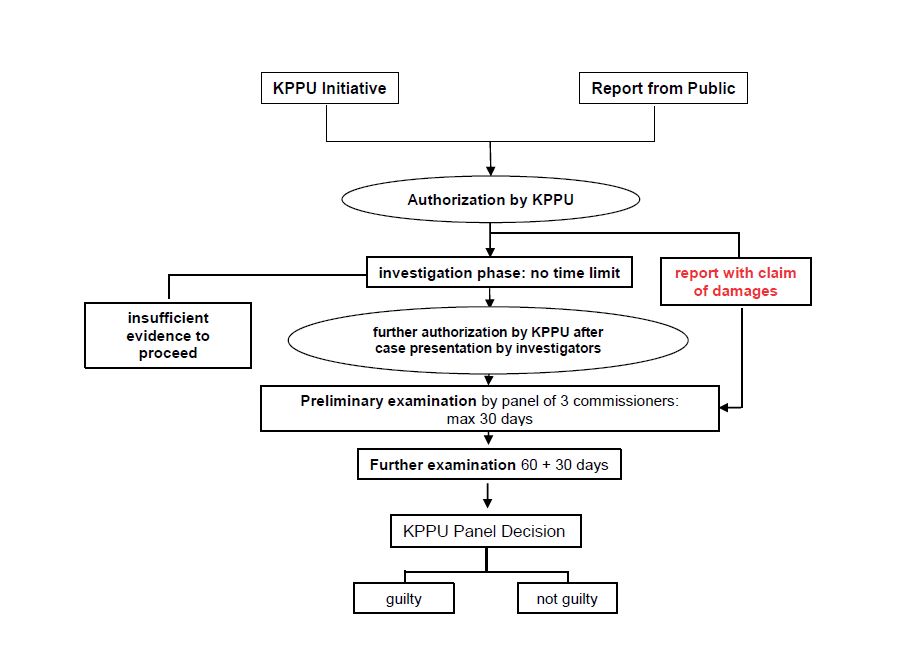

There is also the issue of the burden imposed by the length of KPPU examinations. The Antimonopoly Law imposes a strict time limit for KPPU examination. In total, all stages of examination must be completed within 120 days. In practice this has proven to be inadequate, and so Regulation No. 1 of 2010 introduced a pre-examination investigation phase with no clear time limit. Since then, concerns have been raised that a KPPU investigation may drag on for years before it enters the examination stage during which time business actors have no access to the case files and no certainty on the status of their case. Further, when the case enters the examination stage they continue to be at a disadvantage as they have no right to fully access the case files.

Last but certainly not least is the issue of the KPPU’s acting simultaneously as investigator, prosecutor and judge of their own case. This structure has been criticized as containing a built-in bias in favor of successful prosecution of cases. Cases were investigated by KPPU staff while the Commissioners simultaneously get to decide which cases are to be investigated, monitor the investigation and decide on the outcome of the investigation.

What are the Primary Changes?

The most significant change in Regulation No. 1 of 2019 is the introduction of two new procedures in the preliminary examination phase. Previously, at this stage the examination always had to be concluded at the further examination stage with a panel of three KPPU Commissioners (“KPPU Panel”) issuing its decision on whether a business actor that is being examined (a “reported party”) is guilty.

As can be seen from the table below, Regulation No. 1 of 2019 makes it possible for the process to be ended earlier at the preliminary examination stage if the reported party admits guilt at this stage. In this case, the KPPU Panel will proceed to issue its decision, by-passing the further examination stage.

Further, Regulation No. 1 of 2019 also introduces the possibility of the reported party’s agreeing to make commitments to change its behavior to become compliant with the Antimonopoly Law. Under this option, the examination will be suspended as the KPPU monitors compliance with the commitment given for a period of up to 60 days. If the result of this monitoring is positive, the KPPU panel will issue a ruling certifying the commitments as an “integrity pact”, essentially removing the case out of the examination process. If the result of monitoring is negative, further examination will be initiated.

Overall, these are positive changes that in theory would enable a reported party to take a pragmatic resolution of its situation (e.g., by opting to make commitments), instead of wasting time and resources on trying to win at the further examination stage.

Also, Regulation 1 of 2019 does not have the special process under Regulation 1 of 2010 for handling of cases that arise from a report of violations of the Antimonopoly Law that includes a claim for damages. Under Regulation 1 of 2010 such reports were to be handled in a special examination setting where the KPPU acts like a pure Court that merely adjudicates a dispute between the parties. Under this setting the KPPU does not carry out its own investigation. Rather, the reporting party was supposed to carry out its own investigation. Actually, this process was never undertaken by the KPPU as no reporting party was willing to shoulder the burden of investigating an Antimonopoly Law violation case.

What Are the Primary Issues Remaining?

Unfortunately, Regulation No. 1 of 2019 does not address the due process issues that currently affect the KPPU case handling procedure. As can be seen in the above table, there are a few minor changes that seem to be designed to promote independence of the KPPU Panel. When the KPPU considers whether a case that is being investigated should proceed to the examination stage, the investigators are no longer required to give a full case presentation to the Commissioners. Rather they are required to give a summary to the Commissioners. It appears that the purported effect of this change is that the members of the KPPU Panel do not become invested in the case since they only know its outline and they are expected to find out the details during the examination process.

The problem is the playing field of the examination stage itself continues to be uneven. Regulation No. 1 of 2019 continues to be lacking in due process guarantees. Most significantly, like Regulation No.1 of 2010 it does not guarantee that the reported party will have full access to the KPPU case files. On the contrary, Article 56 (3) of Regulation 1 of 2019 specifies that a reported party and its attorney would have access to examine the authenticity of documents and letters that are used as evidence, but they have to do so under the supervision of the Commission Panel and they are only allowed to make a summary of the contents of these documents. No copying or transliteration is allowed. This provision would make it very difficult for reported parties to challenge documentary evidence that the KPPU uses to support its prosecution.

To be complete, Article 56 also limits the access to documentary evidence to “investigator prosecutors”. Whereas in the past the same investigator who investigates a case also undertakes the task of prosecuting the case at the examination stage, under Regulation 1 of 2019 a different set of investigators is tasked with prosecuting a case. It appears that the argument is that the process is now more fair since the investigator prosecutor also has limited access to the case files and the only ones with full access to the case files are the members of the KPPU Panel. However, this is really beside the point. Under due process, the reported party should have the same access to evidence as the KPPU Panel, not less.

That said, it should be noted that ultimately only an amendment to the Antimonopoly Law can resolve the issues that arise from the current arrangement, whereby the KPPU acts simultaneously as investigator, prosecutor and judge. Unfortunately, the draft amendment to the Antimonopoly Law that is being considered by the House of Representatives is not expected to change this basic structure.