In brief

On 14 May 2020, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) issued its decision on case (C-749/18) further to a request for a preliminary ruling by the Luxembourg Administrative Court on 30 November 2018. The ECJ ruled that the strict distinction made by the Luxembourg tax authorities between the vertical and horizontal tax unity regime is contrary to the freedom of establishment set forth in articles 49 and 54 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

As a result, an EU non-integrating parent entity (i.e., share capital company or permanent establishment) should be able to combine horizontal and vertical tax unity without terminating the pre-existing fiscal unity nor triggering any negative tax consequences resulting from such a termination. Indeed, under Luxembourg current tax consolidation rule, the end of tax unity group before the end of the five years minimum period entails a retroactive tax assessment of each entity on a stand-alone basis.

Contents

Background

1. Legal provisions

Article 164bis of the Luxembourg Income Tax Law (LITL) lays down the conditions of the Luxembourg tax unity regime.

The regime aims at combining the taxable results of each entity[1] belonging to the tax group (the integrated entities) at the level of a single entity (the integrating entity), which is considered the sole taxpayer towards the tax authorities.[2] Losses incurred by one member of the tax group may offset profits realized by other members of the tax group.

At the time the facts occurred in fiscal year 2014, only the vertical form of the tax group was allowed. Furthermore, only Luxembourg resident companies or Luxembourg permanent establishments of non-resident share capital companies were allowed to head a Luxembourg tax group.

Pursuant to the ECJ decision dated 12 June 2014, “SCA Group Holding”[3] (SCA case), the former regime has been amended with effect as of January 2015 by the Grand Ducal Regulation dated 18 December 2015 (GDR). The GDR introduced the possibility to create a horizontal tax group where eligible Luxembourg resident sister entities could form a tax group with their common (direct or indirect) parent entity (the non-integrating parent entity).[4]

Among other conditions to benefit from the tax unity regime (irrespective of whether under the former or the new regime) all entities have to file a joint request[5] prior to the end of the first fiscal year for which the regime is requested whereby they commit to be part of the tax group for a period of at least five years. Note as well that an entity cannot belong simultaneously to different tax groups.

2. Facts of the case

A Luxembourg tax resident company (B) was fully owned by a French tax resident company (A).

As from fiscal year 2008, company B formed a tax group with certain subsidiaries in accordance with article 164bis LITL (vertical group). Over the years, the tax group has been extended to several other subsidiaries of B.

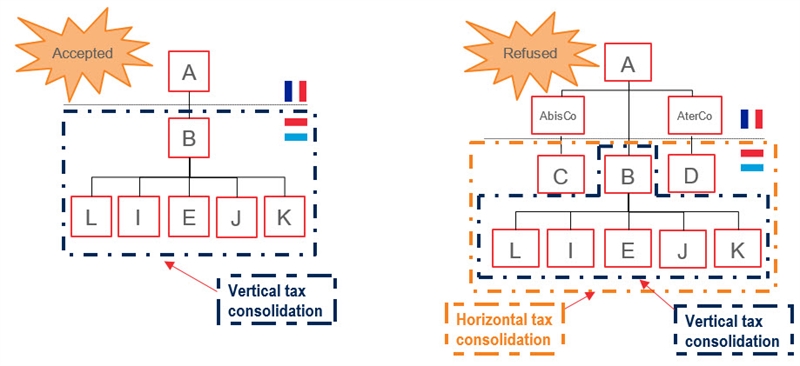

In 2014 and further to the SCA case, companies C and D (being sister companies of B and indirectly held by company A) applied to join the existing (vertical) tax group thereby extending the group horizontally (company A being the non-integrating parent company). The companies filed two letters on the grounds of the SCA case. The first letter aimed at extending the tax unity regime to C and D retroactively as from fiscal year 2013 while the second letter requested the application of the tax unity regime as from fiscal year 2014.

The Luxembourg tax authorities rejected both requests. The first request has been dismissed as filed after the due date (i.e., after 31 December 2013). On the second request, the tax authorities considered (in line with the intention of the legislator[6] resulting from the parliamentary documents linked with the GDR[7]) that the horizontal and vertical form of the tax group were alternative, so that the two forms were mutually exclusive. A change from one form to the other was analyzed as automatically ending the existing tax group. In this respect, the tax authorities also argued that a single entity could not belong to different tax groups.

Illustrative charts

The companies then brought the case before the Luxembourg judges.

On 6 December 2017, the Administrative Tribunal decided that the first request had to be rejected since the time limit set forth by the law had not been complied with (i.e., filing of the request before the end of the first fiscal year for which the tax consolidation is requested to apply). However, on the second request, the Administrative Tribunal ruled that article 164bis LITL (in its version prior to GDR amendments) was contrary to the EU freedom of establishment. The tribunal concluded that the former regime induced a discrimination as it precluded a non-resident (non-integrating) parent entity residing in another EU member state (i.e., France) to extend the tax unity to all its Luxembourg eligible resident subsidiaries whereas this was possible for Luxembourg resident parent entities without jeopardizing the whole tax group.[8]

On 15 January 2018, the companies appealed the decision before the Administrative Court. The latter raised serious doubts regarding the compatibility of the Luxembourg tax unity regime with EU law and referred the following three questions for a preliminary ruling before the ECJ:[9]

-

-

- Is the tax consolidation regime provided for by article 164bis LITL (as applicable until fiscal year 2014) contrary to the EU freedom of establishment?

- If the answer to question 1 is positive, is the strict separation between vertical and horizontal tax unity groups resulting in the termination of a pre-existing (vertical) tax group triggering adverse tax consequences contrary to the EU freedom of establishment?

- If the answer to question 2 is positive, is the time limit required under article 164bis LITL to request the admission to the tax unity regime contrary to the EU freedom of establishment and the principle of the effectiveness?

-

ECJ’s ruling

1. Former article 164bis LITL found to be discriminatory

The ECJ found article 164bis LITL to be discriminatory since EU parent (non-integrating) entities were treated at a disadvantage compared to Luxembourg parent entities.

On this point, the decision of the ECJ is not surprising as it is in line with the SCA case. It is notable that the Luxembourg legislator already took necessary actions back in 2015 (through the GDR) to align the Luxembourg tax unity regime with EU law and principles.

2. The change from vertical to horizontal form of the tax group should not imply the end of the pre-existing tax group

The ECJ ruled that the strict separation between vertical and horizontal tax unity as applied by the Luxembourg tax authorities was contrary to the EU freedom of establishment because the restriction was not justified by overriding public interest.

As such, an extension of the tax group entailing the automatic dissolution of an existing tax group and resulting in negative tax consequences (i.e., retrospective tax reassessment on a stand-alone basis) is discriminatory and cannot be upheld, particularly when the integrating company remains the same.

The ECJ stresses the central role of the integrating entity with the tax group. Therefore, as long as the integrating entity remains the same and (of course) provided that the other conditions are met, an extension of the tax group or a restructuring within the tax group does not entail the dissolution of the tax group.

3. Formal aspects of tax unity request has to be respected

Finally, the ECJ confirmed that the time limit required under article 164bis LITL to request the benefit from the tax unity regime is not in breach of EU principles.

Therefore, corporate taxpayers that want to apply for the tax unity regime should carefully consider the timing for the application request. In any circumstances, the request has to be filed before the end of the first fiscal year for which the tax unity regime is requested.

Impact in Luxembourg

Case law ruled by the ECJ are binding both in the referring court and in all courts in EU member states. More precisely, the judgment of the ECJ shall be binding from the date of its delivery. Accordingly, the Luxembourg tax authorities and Luxembourg courts will have to follow this decision.

Often the conditions to apply for or to maintain the tax unity regime raises complex issues in practice. In particular, in the framework of restructurings disruptions of the conditions may happen and result in significant adverse tax consequences, especially when the five year minimum period has not been reached yet. As such, a careful tax analysis should always be sought. Our Baker & McKenzie tax lawyers are at your disposal to help you dealing with these matters.

[1] Luxembourg resident share capital company or Luxembourg permanent establishment of a non-resident share capital company subject to tax comparable to the Luxembourg corporate income tax.

[4] EEA share capital company subject to tax comparable to the Luxembourg corporate income tax, EEA permanent establishment of a share capital company subject to tax comparable to the Luxembourg corporate income tax, Luxembourg share capital companies and Luxembourg permanent establishment of a non-resident share capital company subject to tax comparable to the Luxembourg corporate income tax.

[6] As analyzed by the Administrative Court, 29 November 2018 (40632C).

[7] Parliamentary documents 6847, p.11.

[8] As an example, in the case law dated 24 June 2015, the Luxembourg Administrative Tribunal ruled that the tax authorities could not treat the admission of a new member of the group as giving rise to a new integrated group.